|

Field Strength Meter MkI |

Essential for checking the output of our FM transmitters

This Field Strength Meter has been specially designed for our FM bugs. It is capable of detecting very low power transmitters and will assist enormously in peaking many of our FM transmitters that have a coil in the output stage that can be adjusted for optimum output.

|

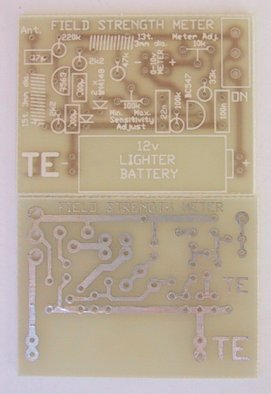

A close-up of the Field Strength

Meter MkI connected to a multimeter |

|

A close-up of the circuit Board showing the the position of the components |

|

Field Strength Meter MkI Circuit. A 2N2222A transistor can be used in either/both locations |

Up to now, field strength meters have only been able to detect

transmitters with an output of 100 milliwatts or higher, and for an output

such as this, a simple circuit such as a meter and a coil is sufficient. But

when it comes to a low power device, a simple circuit, with no amplification,

is not suitable.

We spent more than 5 days building all the circuits we could find - that purported to be suitable for low-power transmitters, hoping

to find one that would work.

Unfortunately none came anywhere near good enough so we had

to design our own.

The circuit we came up with is shown above and it

incorporates an RF amplifier, diode rectification, and a DC amplifier so that a

movement from a multimeter (a movement is the 'meter' part of a multimeter)

could be used as the readout. The heart of the design is a pair of diodes that

are partially turned on via a resistor (the 100k sensitivity control) and this

overcomes some of the .6v threshold of a diode.

You may not think .6v is very much but when you are talking in millivolt terms,

it is 600 millivolts. The signal we are attempting to pick up produces one or

two millivolts on the receiving antenna and if you need 600 millivolts to turn

a diode ON, the field strength meter becomes very insensitive.

Our design overcomes this problem and produces a reading up to 10cm from a bug.

This means you can adjust and peak a bug with the antenna fitted and get an

accurate indication of the power it is producing.

Up to now you have had to rely on the "LED Power Meter” as described in

a previous article and although it gives a good indication of the RF

energy, it does not take into account the loading effect of the antenna.

The antenna loads the output stage of any transmitter and when you have a low

power device, the antenna tends to detune the frequency slightly

so that a slight re-peaking is necessary if you want to get maximum

performance. The field strength meter will allow you to do this and get back

the extra performance you may have lost.

HOW THE CIRCUIT WORKS

The circuit consists basically of an RF amplifier, diode rectifier and a DC

amplifier. The first feature that may be new to you is the inductor in the

antenna circuit. You may think it produces a short-circuit between the antenna

and earth but the inductance of the 15 turn coil creates a voltage across it

when the antenna picks up a signal. This voltage is fed to the base of the

first transistor via a 47p capacitor and since the transistor is turned on via

a 220k resistor, any signal from the 47p will be amplified by the transistor.

The RF amplifier has been designed to only have a gain at high frequencies. In

our case this is at about 100MHz to 300MHz. The 300MHz is the upper limit due

to the response of the RF transistor and the lower frequency is governed by the

100p bypass capacitor on the emitter.

It's impedance at 100MHz is 16 ohms and this gives the stage a gain of about

12. At 10MHz the reactance of the capacitor is 160 ohms and the gain of the

stage drops to about 2.

This prevents low frequencies from being amplified and up-setting the reading.

By increasing the value of the emitter bypass capacitor, the gain of the stage

will be increased but this is not desirable as it may cause excessive gain

causing the front end to self-oscillate.

The inductor in the collector circuit separates the output signal from the

power rail and increases the output amplitude slightly.

The low value coupling capacitor (100p) between the RF stage and diode pair is

sufficient to transfer the energy as, don't forget, we are dealing with very

high frequencies. The two diodes in the diode stage simply work as a rectifier

and are partially forward biased via a 47k and 100k sensitivity control from

the positive rail. But they are not turned on fully due to the base emitter

junction of the DC amplifier transistor only allowing .6v to appear across

them.

When a signal is passed into the diode pair, the negative excursions

reduce the voltage across them and this begins to turn off the DC amplifier

transistor and thus the needle on the meter drops. It requires about 300mV

signal to start the process and with a gain of about 12 on the RF transistor,

we need about 30 millivolts developed on the antenna circuit to start the

detecting process.

This makes the Field Strength Meter only sensitive to nearby

signals and prevents weaker signals from upsetting the reading.

The 10k pot connected to one end of the voltmeter sets the full-scale

deflection for a 0-10v range on the multimeter.

The circuit consumes about

3.5mA and with a lighter battery (50mAHr cells) the circuit will operate for

more than 12 hours. A switch is provided to conserve the battery when not

required and the board attaches to any multimeter via leads and paper clips

that have been bent to suit the banana sockets on the meter.

Any old meter will do and it can have a sensitivity from 1k ohms per volt to

50k ohms per volt. The range we used in our prototype is 10v DC on a 30k ohms

per volt meter however 12v, 15v or even 25v scale will be ok and the 25v range

simply means the needle will not deflect as much, for the same RF detected.

You can even use an old, broken, multimeter providing the movement is not

damaged. We have about 5 of these field strength meters, one for each

worker, as everyone needs one to peak the devices we are making

We turned 5 broken multimeters into active service. It's one good way of using damaged equipment. It's amazing how the staff can blow up things, with the

ohms range not working and the milliamp range burnt out.

I remember one firm had the same problem. They made all the staff spend every Friday afternoon repairing the test equipment but with the tight

economics of today, we couldn't afford the luxury of providing half a day's

holiday like this each week.

|

Field Strength Meter Mk I Kit |

|

PARTS LIST |

|

2 - 2k2 1 - 33k 1 - 47k 1 - 100k 1 - 220k 1 - 47p ceramic 2 - 100pceramics (101) 1 - 22n ceramic (223) 1 - 100n ceramic (104) 1 - 10k mini trim-pot 1 - 100k mini trim-pot 1 - BC 547 transistor 1 - PN 3563 RF transistor 2 - 1N4148 diodes 1 - 13t enamelled wire 3mrn dia coil 1 - 15t enamelled wire 3mm dia coil 1 - 12v lighter battery 1 - 25cm enamelled wire 1 - SPDT mini slide switch 2 - paper clips 1 - FIELD STRENGTH METER PCB |

|

Extras: |

| 1 - multimeter (0v -10v range) |

|

Field Strength Meter MkI PCB |

CONSTRUCTION

All the components, including the 12volt lighter battery and switch, mount on

the PC board. The legend on the board shows where each part is placed arid we

have found it important to avoid over-heating the diodes and transistors as

they lose their peak performance and cause the circuit to become very

insensitive. Follow the overlay on the PC board to see where everything is

placed. The coils are pre-wound in the kit and are wound on a 3mm diameter

Philips screwdriver (if you are making your own) and the wire size is not

critical as they simply form a broad-band trap.

The antenna wire is enamelled to prevent it touching the active components of

the bug you are testing.

We needn’t say any more about construction as you will obviously know how to

put the kit together.

SETTING UP

Solder the paper clips to the board as shown in the photo and bend them to suit

the sockets on the multimeter. Turn the "sensitivity" control (100k pot) to

minimum resistance and switch the circuit ON. Turn the "Set full scale

deflection" pot (10k) to give full deflection on the meter. Now turn the

sensitivity pot until the needle just starts to "dip."

At this point the circuit is the most sensitive as the DC amplifier transistor

is just turned on and any signal appearing on the diodes will reduce the

voltage appearing on the top of them and turn the transistor off - the needle

on the meter will begin to drop. The Field Strength Meter is now ready for use.

USING THE FIELD STRENGTH METER

This project will help you get the best silt of any transmitter. It will give

an accurate readout because it does not connect to the transmitter but

registers the strength of the field AT A DISTANCE.

The way it is used is to set up the antenna of the Field Strength Meter in the

same plane as the transmitting antenna (to get the best pick-up) and at a

distance that just causes the needle on the meter to deflect.

The meter is wired as a "DIP" meter and the needle deflects towards zero as the

field strength increases. Place the bug to be peaked on the test bench, with

the antenna out-stretched and bring the receiving antenna so that the needle just

starts to dip.

Peak the circuit a small amount and take your hands away so that they don't

upset the reading, and watch the needle. As the output increases, the needle

dips further. By maintaining the exact same distance between bug and meter, you

can compare one bug with another.

It's the fastest way of determining the output without doing a "field test."

IF IT DOESN'T WORK

As with all our projects, they work be cause we have actually built them and

checked their performance. If yours doesn't work, the first thing to do is

check the value of the components against the overlay on the board.

Two components in the wrong place can make a huge difference and a circuit like

this is fairly critical as the biasing must be correct.

Secondly, make sure all the parts are fitted and nothing has been missed. Also

make sure all the parts have been soldered neatly and cleanly.

We still get projects sent to us for repair where one or more leads have not

been soldered and obviously the project could never work.

Next you can make a few voltage readings. Although they don't tell you too

much, it is a fast way of determining if a stage has the correct DC conditions.

| The voltages: |

| RF Stage: |

| Collector:

6.1v Base: 5.8v Emitter: 5.2v |

| DC stage: |

| Collector:

0.2v Base: 0.65v Emitter: 0v |

If these check out ok, you should make a few further DC tests. If the meter

swings full scale at power-up, you should short between base and emitter of the

BC 547 to see the needle falls to zero. This will show the transistor is

working ok. If not, the transistor may be shorted.

Next remove the 47k on the diode pair. This will also cause the needle to move

down-scale and show the biasing network is working. It is more difficult to

test the RF stage and merely probing around the stage with a meter or CR0, will

pick up hum and cause the needle to deflect.

Of course we have assumed you have bought a kit and PC board for the project.

The frequency of operation of this circuit makes it important that it is built

on the correct PC board.

We cannot guarantee "breadboard" jobs or circuits made with your own components

as so many variables creep in.

Things like different markings on capacitors, different RF transistors or

signal diodes could make the difference between success and failure.

If you know what you are doing, that's fine - you can use your own components.

But if you intend to learn from our projects, don't take any chances. It's

cheaper in the long run to get all the projects in kit form and build them

exactly as specified.

If you get really stuck, don't hesitate to buy another kit and start again. You

can come back to the faulty one later. This project is so important that we

don't want you to miss out. With a field strength meter you can carry out

experiments that would take a chapter of a book to explain. Here's one:

EXPERIMENTING

Take the Voyager project and connect 30cm of tinned copper wire to the antenna

point on the PC board. Hold the Field Strength Meter in your hand (keep away

from the actual circuit by holding the multimeter) and bring the receiving

antenna near the Voyager antenna, without touching it. As you move up and down

the Voyager antenna, watch the needle.

It will show that energy is not radiated uniformly from the antenna but has a

maximum and minimum value. It is for you to see where these occur. Measure the

length of the antenna and plot the results. Cut 2cm off the antenna and repeat

the tests. Fit a 175cm antenna to the bug and repeat the tests.

This will give you a good understanding of the phenomenon of electromagnetic

radiation.

There are lots of other things you can test with this project.

The Field Strength Meter Mkll is presented in the next article and has the

advantage of a tuned front end and 3-LED readout. This will enable you to not

only peak transmitters but also find the frequency on which they are operating.

It detects in the range 75MHz to 140MHz enabling you to design and build

transmitters capable of transmitting off the normal broadcast band.

But don't put off building this project as you will need both of them as they

have different capabilities. And you also need the LED Power Meter.

Test equipment is very important when working with RF so don't put it off any

longer, start now and build up your range of gear.