|

THE

MICRO BUG |

$14.50 incl all parts and PCB

plus $3.50 postage to anywhere in the world

to: P1 P2

![]()

|

|

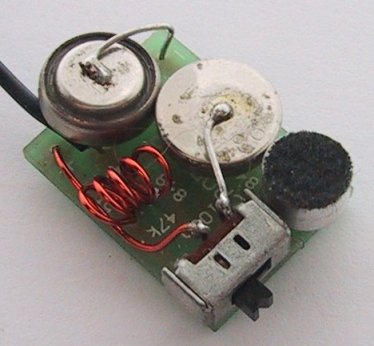

Another view of the underside of the Micro |

Even though the transistors are designed to withstand 10 seconds of soldering

in a wave-soldering machine, this does not mean you can take 10 seconds to

solder with a soldering iron.

The reason is the wave-solder bath is maintained at a precise temperature

and this is the exact temperature to complete the

soldering process without overheating the components.

Most soldering irons are above this temperature and this means the soldering

time must be reduced. For an iron 30°C above this temperature, the time must be

reduced to 3 seconds and for 50°C above, the time must be less than 1/2 second.

Most hobbyist irons come into the 1/2 second category and on top of this, only

one lead at a time must be soldered.

Once you know your soldering techniques are acceptable for surface-mount

components, and none are being damaged, you can you can work as fast as our

assembly section and fit the components about twice as fast as the through-hole

variety.

|

|

|

The Micro Bug

with two button cells soldered to the top of the board with a

miniature slide switch. |

|

|

The pinout of the SM transistor we supply in the kit |

THE SURFACE MOUNT TRANSISTOR

Now let's talk about the surface mount transistor.

When you open up your kit of parts you will get quite a shock.

The surface mount transistor is smaller than you think and in fact I think it

is too small for manual insertion. But that’s what you’ll have to face.

Certainly the designers of surface mount transistors had no intention of them

being inserted by hand as they are smaller than a surface mount resistor!

But any industrial prototypes have to be assembled by hand and this project

will be a good experience for later.

Above you see the outline of the surface mount transistor. The top of the

device is too small to fit the full type number and a silly code number has

been allocated as follows: BC 847, BC848 (NPN) is marked 1k, but most importantly it

is a three leaded package.

This is the same as BC 547. The tiny leads are so short that they just emerge

from the case and this means any heat from the soldering iron will travel to

the junction very quickly. You have only half a second to complete each solder

joint. Any delay will damage the transistor totally and it will fail to

amplify.

TESTING and GETTING THE CIRCUIT TO WORK

THE LED POWER METER

We are going to cover these two at the same time.

Testing the circuit and getting it to transmit on a particular frequency is

a learning experience. If the circuit does not work, this

is when you will start to learn REAL electronics.

I hope the circuit does not work and you have to fix it, but since our projects

have been tried and tested thousands of times, the chances of it not working

are very slim. The main fault will be overheating the components and damaging

them by trying to move them while soldering.

As I have said, this transmitter is an advancement on a number of projects we have already presented and it has been suggested that you build

some of the others to get you accustomed to the performance.

The first thing to do is see if the transmitter works (transmits).

Place it near an FM radio turned to medium volume and tune across the dial,

listening for a feedback squeal.

If a squeal is heard, the transmitter is operating on the FM band. If you don't

hear a squeal, don't worry as the circuit may be operating just

below the band and in this case you will not be able to pick it up.

To find out, remove the antenna lead and fit the

LED Power Meter.

It will only take 10 minutes or so to build this circuit and connect it to an

ordinary multimeter set to low volts range.

Once you have built it, you can go on to the next stage:

The LED power Meter is a simple RF detector using diodes to charge a capacitor.

The voltage developed across the capacitor is shown on a multimeter set to a

low voltage range.

The circuit is soldered together without the need for a PC board, as can be seen in diagram below and paper clips are used for the positive and negative terminals of the multimeter.

The output of the Micro Bug is very low and you will only get a

very small indication on the meter and a very small glow from the LED.

The reading is not calibrated and does not represent milliwatts output. It is

only a visual indication.

|

LED Power Meter Parts List |

| 1 - 470R (yellow-purple-brown) 1 - 100p ceramic (marked 101) 1 - 0.1u (100n) ceramic (called monoblock) (104) 2 - 1N 4148 diodes 1 - 2in (5cm) hook-up wire 2 - paper clips No PC board required |

If the multimeter does not show a reading, the output stage is not working.

The two stages in this project are AC coupled (a capacitor separates them)

and they can be tested separately.

The first place to go to is the oscillator section. This is called and RF

oscillator as it is operating at approx 88MHz.

This is a difficult stage to test as it is operating at a very high frequency.

It is not possible to view the waveform on an ordinary 30MHz CR0 as the circuit

is operating at 88MHz and the CR0 will not display the waveform on the screen.

All it will show is a mass of lines

- if you are lucky. A 30MHz CR0 will also put such a load on the circuit that

it will cease to oscillate.

This means all you can do is take a few voltage measurements and check the

continuity of the trackwork.

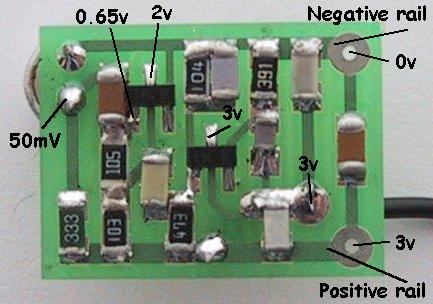

Firstly check the voltage on the collector of the oscillator transistor. It

should be 3v, indicating the coil is making contact through the board. Next

measure the voltage on the emitter. It should be about 2v. If it is 0v, the

transistor is not being turned on or the 390R is not making contact with the

board (the voltage will be about 2.5v to 3v, in this case). The base voltage

should be about 2.6v, and if it is much lower than this, the 47k resistor may

be the wrong value or the transistor is pulling the voltage down (due to the

emitter resistor being the wrong value and/or the base-emitter junction being a

short circuit).

|

|

A guide to the voltages on the Micro Bug |

When you are probing around this stage, the load produced by the leads of the multimeter will often prevent the circuit from operating, so don't expect to get an output on the LED Power Meter when probing the board.

The main reason for this is the leads become an antenna and they absorb the signal.

The LED Power Meter can be connected all the time. It puts a very small load on the circuit and will not affect the performance.

The test-points on the PC

board

referenced to the circuit.

This will help enormously when fault-finding.

Click photo for large diagram.

Two problems remain. You cannot test the 47p unless you remove it and test it on a

Capacitance Meter. The same applies to the 10p. The cheapest and quickest thing

to do is replace the two components (the surface mount components are available

as spare parts).

The 1n is also very important and if it has been damaged during assembly (open

circuit), the oscillator will not function. This should also be replaced.

Lastly the 22n across the power rails must be in place to get a good output

from the oscillator. Try another 22n across it to see if the performance

alters. The only other things I can suggest are a shorted or damaged 100n input

capacitor and/or a damaged transistor.

Removing the transistor and testing it will be almost impossible as the heat

required to desolder the leads will destroy the component.

The only real choice is to replace the transistor and make sure you solder it

quickly.

Obviously you will have checked the freshness of the button cells, to make sure the

voltage is not too low, and the operation of the switch.

Just in case you are not aware, you cannot connect this project to a power

supply or to cells via long leads. The length of the leads will reduce the

"tightness of the circuit” and prevent the oscillator from functioning

properly.

This should get the oscillator functioning and you can now go to the antenna

point and measure the RF via the LED Power Meter.

You must get a reading (a slight reading) on the antenna-point before continuing.

SETTING THE FREQUENCY

The next step is to set the frequency of operation.

This could be below the FM band or above it as the commercial section between

88 and 108MHz is rapidly filling up.

When we first started producing transmitters the band was almost totally empty,

but as minority groups have begun to realize the power of voicing their view on

the airwaves, every local community group has its own radio station.

The separation between radio stations is now less than 100kHz and you cannot

get another transmission in between.

Just above or below the dial is sometimes the best solution and we have opted

for below the band when we sell made-up devices, as the range is better.

Simply by adding one more turn to the oscillator coil we can tune below the

band and adjust the turns to sit between courier companies and other users.

When thinking of transmitting above the band, you cannot operate between 120MHz

and 130MHz as this has been allocated to the emergency band and aircraft

traffic control.

With a reading on the LED power Meter you know the Micro Bug is transmitting

but you don't know the frequency of transmission.

If you want to operate on the 88 -108MHz band, turn on an FM radio and tune

across the band. When the radio is at the same frequency as the Micro Bug, it will

produce a loud squeal.

If you want to operate below the band you will have to detune the radio so that

it will go down to approx 86MHz.

This is done by moving the turns of the air-cored coil near the tuning gang so

that the stations move up the scale. This will create an empty spot at the

lower end of the band. You can also adjust the trimmers on the back of the

tuning capacitor to shift the stations up or down the dial.

In most cases you cannot shift the band very much as the stations begin to

"wrap around” the dial and the high stations appear at the lower end. Be

satisfied with a small shift. You should now tune the radio to the bottom of

the band if you have detuned the radio, or to the top of the band if you have

moved the stations down.

For a detuned Micro Bug, you should have 7 turns in the oscillator coil. Move the

turns of the coil so that you get a feedback whistle.

If you want to transmit above the commercial band, make sure you have 5 turns

on the coil.

One of the main problems with this part of the operation is finding the

frequency of transmission. The LED Power Meter will not give you this; it will

only let you know when the oscillator is operating.

You need a frequency meter or our FIELD STRENGTH METER MklI (to be described in

a future issue). It has a scale marked on the PC board, from 75MHz to 140MHz to

let you know the frequency of the signal you are picking up and a set of 3 LEDs

to indicate the relative strength of the signal.

If you get a reading on the LED Power Meter and an indication on the

Field Strength Meter Mkll to indicate the frequency is say 90MHz, but the radio

only produces a dead spot or quiet spot on the dial, it will indicate the audio

from the first stage is not coming through.

This means the fault will lie in the audio amplifier stage and/or electret

microphone. The first thing to do is take voltage tests and confirm your

readings against those given on the circuit diagram. The collector of the audio

transistor should be about half rail voltage (and the voltage on the microphone

can be as low as 50 millivolts) and the microphone will still be working

perfectly.

To test these stages more fully you need an audio oscillator or audio probe and

we have provided an audio injector probe on the

Combo-2 project.

Connect the earth clip of the Combo-2 project to the negative rail of the Micro

Bug

and inject a signal at the collector of the audio stage.

This will send a tone through the 100n coupling capacitor and produce a buzz

from the radio.

If this does not happen, the fault will lie in the 100n monoblock or maybe the

end of the capacitor that goes to the collector of the audio stage has a short

under the board, taking it to one of the rails and thus shorting out the

signal.

Once you get a signal at this point, move the probe to the base of the audio

transistor. The buzz from the radio should be louder.

If it is weaker, the audio transistor may not be amplifying correctly. It may

be damaged or open circuit.

Next, take the audio probe to the output of the microphone. If the output from

the radio is reduced, the 22n coupling capacitor may be open circuit or one of

the ends may be shorted to the negative rail.

If the output point of the electret microphone produces a loud buzz from the

radio, but the microphone does not produce any audio, the most likely cause is

a faulty microphone. Check around the microphone for shorts and solder bridges.

As a last resort, replace the microphone.

CONCLUSION

This completes the project. It is about as small as you can get and if you

have a fine-tipped soldering iron, it should be possible to get it working,

provided you follow our instructions carefully.

You will be very pleased when you turn it on as it will pick up the ticking of

a clock and anyone whispering nearby.

Surface-mount components are excellent for this type of project.

High-frequency projects like to be very compact as it improves the "Q-factor"

(the overall output of the oscillator stage) and surface-mount components

make the circuit very "tight."

Once you start working with surface-mount, you will realize it is the only way

to go.

We will be presenting more surface-mount projects in the future, keep looking

out for them.

![]()